Earlier this week, researchers at Nottingham University were able to recreate a 9th c Anglo-Saxon medical remedy using garlic, onion and part of a cow’s stomach. When I first heard about this, it sounded like one of those horrible medical remedies discussed on Sawbones that doesn’t actually work. But here’s the crazy part- this Anglo-Saxon cure known as “Bald’s eye salve”, a mixture of onion, garlic, leek, wine, cow’s bile and cow’s stomach, actually works for wiping out methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus, known as MRSA. MSRA is a bacteria that is resistant to many antibiotics, and can cause anything from skin infections to widespread infection and pneumonia.

This is a fascinating turn of events, and has lead to some questions about whether or not we should be reconsidering some medicines from the past. And of course, because cow stomach was part of the MRSA remedy, there have been questions about whether corpse medicine may have actually had some effect on health and whether it actually cured anything.

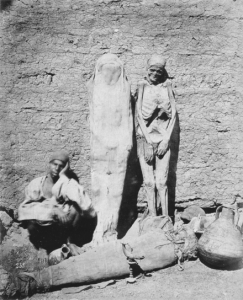

Corpse medicine, or medical cannibalism, is the act of using parts of deceased humans for medicinal reasons. This persists today in such acts as organ transplant and blood transfusions. However, in the past, corpses were used for a wide variety of medical purposes and were thought to be able to cure anything from bleeding to aging to epilepsy. One of the most popular ways of ingesting human remains for health benefit was by using mummia, or the dried remains of a mummy which has been prepared for medical use.

In the 17th century, Puritan Edward Taylor, a follower of Paracelsus medicinal practices (I suggest this episode of Sawbones for learning more about Paracelsus), valorized the use of mummy as a medical remedy as it was an appropriate substitute for the body and blood of the sacrament. Paracelsian doctors believed that spirits and occult influences could have a healing effect, so the body of the dead would be able to heal the best. Doctors following Paracelsus also believed that like cured like, so to help with headaches, you could ingest the powdered skull of a dead man. Taylor used his mummy medicine throughout New England, and his medical books list the various uses of these parts: a dried heart would cure epilepsy; the skin from a mummy would help stop bleeding and restore the flesh; dried gall bladder powdered and mixed with wine could help with deafness. Mummy was seen as the universal panacea among the followers of Paracelsus, especially Puritan Taylor.

This medicine wasn’t just used in New England. All across Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, mummy was a hot medical commodity. Thomas Willis, a 17th-century pioneer of brain science, believed that a drink of hot chocolate and powdered human skull could help with apoplexy or bleeding. King Charles II of England had a special drink known as the “King’s Drops”: a personalized mixture of human skull in alcohol. German doctors argued that the fat from the deceased could be used to help with gout, by rubbing bandages in the fat and wrapping them around the effected areas. In 1618 the English College of Physicians included mummy and human blood in the official London Pharmacopoeia, and medical texts continued throughout the 18th century to include human body parts as cures and medicines.

Of course, since mummy was such a fashionable medicine, it could often be hard to get. There are only a limited amount of mummies in the world (with the Egyptian and African ones being the most prized). When mummies were in short supply, Edward Taylor knew how to create his own, as he had been taught following a recipe from Oswald Croll:

“Take the fresh, unspotted cadaver of a redheaded man (because in them the blood is thinner and the flesh hence more excellent) aged about twenty-four, who has been executed and died a violent death. Let the corpse lie one day and night in the sun and moon- but the weather must be good. Cut the flesh in pieces and sprinkle it with myrrh and just a little aloe. Then soak it in spirits of wine for several days, hang it up for 6-10 hours… Thus they will be similar to smoked meat, and will not stink.”

Traders in the Mediterranean took this one step father, and cashed in on the mummy medicine trend by preparing fake mummies. They would take the bodies of dead lepers, beggars or criminals, and prepared them in ways that would make them look like ancient Egyptian mummies. The problem with this, is that it could actually cause more diseases- certain viruses can survive in the deceased, like plague, and would be ingested by wealthy health seekers.

While a mixture of onion, garlic and cow’s stomach may wipeout MSRA, I don’t think we should be returning to the practice of corpse medicine. As Richard Sugg noted, in the past “numerous surgeons or physicians would press or sprinkle powdered Egyptian mummy, powdered blood or powdered moss of the skull onto a bleeding wound. This probably did work – but only because powder stimulates coagulation. The forensic pathologist who explained this to me added that, when his little brother suffered a bad head cut in childhood, their mother simply put powdered coffee on the wound.”

A big thank you to Dorothy King Lobel for sharing journal articles with me on this topic and inspiring this post. If you’d like to learn more about this, check out these great resources:

Mummies, Cannibals and Vampires: The History of Corpse Medicine from the Renaissance to the Victorians by Richard Sugg

A medieval remedy for MRSA is just the start of it. Powdered poo, anyone? by Richard Sugg from The Guardian

Drinking Blood and Eating Flesh: Corpse Medicine in Early Modern England by the Chirurgeons Apprentice

The Gruesome History of Eating Corpses as Medicine by Maria Dolan on Smithsonian.com

References

![]() Gordon-Grube, K. (1988). Anthropophagy in Post-Renaissance Europe: The Tradition of Medicinal Cannibalism American Anthropologist, 90 (2), 405-409 DOI: 10.1525/aa.1988.90.2.02a00110

Gordon-Grube, K. (1988). Anthropophagy in Post-Renaissance Europe: The Tradition of Medicinal Cannibalism American Anthropologist, 90 (2), 405-409 DOI: 10.1525/aa.1988.90.2.02a00110

Karen Gordon-Grube (1993). Evidence of Medicinal Cannibalism in Puritan New England: “Mummy” and Related Remedies in Edward Taylor’s “Dispensatory” Early American Literature, 28 (3), 185-221

Bernal Diaz del Castillo, in The True Account Of The Conquest Of New Spain, recounts that he and his fellow invaders treated their numerous wounds by rubbing or pouring in the fat of dead mounts and pack animals. Diaz also states flatly, more than once, that the fat of recently killed natives was resorted to in the absence or inexpediency of the preferred sources.

Excellent and morbid example, love it!

Cool post. Corpse medicine reminds me of how pituitary glands were once harvested from cadavers and used to treat folks with growth hormone deficiencies. A couple of cases of Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease put an end to that practice!

Nice example! Thanks for sharing!

Oh my God, I’m all for the medical discovery that can help people get cured.

I don’t know if I want to ingest something human, then again, if I get sick and I’m desperate to get better, why not?

Thank you for sharing.

I agree with the previous comment about the Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease. I wonder if ingesting that corpse medicine won’t have side effects like the Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease.

Reblogged this on ATWA and commented:

Morbid but very interesting. Redheaded man, coincidence? Rh negative type blood? Maybe? “Take the fresh, unspotted cadaver of a redheaded man (because in them the blood is thinner and the flesh hence more excellent) aged about twenty-four, who has been executed and died a violent death. Let the corpse lie one day and night in the sun and moon- but the weather must be good. Cut the flesh in pieces and sprinkle it with myrrh and just a little aloe. Then soak it in spirits of wine for several days, hang it up for 6-10 hours… Thus they will be similar to smoked meat, and will not stink.”

Reblogged this on HBPR.

Reblogged this on deductiondetective and commented:

‘You see, but you do not observe. The distinction is clear.’